Sonic Gift-Giving on TikTok

Since the advent of COVID-19, Algerian youth, artists, and studios have taken to TikTok to sell, promote, and binge-listen to the latest raï hits. So called «sonic gifts» are remarkable in this context, as they show that young people’s music consumption is not simply the result of algorithmic content curation or commodity exchange. Rather, as I argue in this commentary, TikTok cultures enable the use of sound in spontaneous ways. Studying sonic gifts is meaningful because these gifts reveal the complexity of how people build relations and reputations in digital media spheres.

While conducting fieldwork on TikTok usage among Algerian youth, I participated in trends where people combined «audio memes» (Abidin and Kaye 2021) of raï songs with lip-synching and the local dance style way way. This performance style originates in the playgrounds, wedding halls, and cabarets of urban districts (Bouziri 2014). Singers like Chaba Warda Charlomante and microcelebrities like Choukri Pirate have attracted thousands of followers through performances to new raï. Some Algerians frown upon these TikToks, while others are proud to creatively spread their «sensory knowledges» (Hirschkind 2006). TikTokers derive social capital from dancing to anthems. They gain likes, gratitude, and followers, and establish bonds with others. One unique way for young people to engage in musical sociality is through didikas: what I call «sonic gifts».

From Cabaret to TikTok

I first encountered didikas in the comment section of an account whose TikToks I enjoyed watching. Didikas (Arabic phonemic orthography for the French word dédicace) literally translates as dedication, but also means request. It originated in radio shows and cabarets featuring raï performances, where audiences offered money to the singer (or a middleman) to praise their family or people present and perform their favorite song (Schade-Poulsen 1999, 47). This long-standing ceremonial act has spread to digital media, where audiences can request a didikas by commenting on a TikTok. Contrary to the cabarets, there is no money involved in this exchange, nor is it a competitive game where people make bids to get their tune played. Instead, it is a pleasurable gift-giving exchange.

The Soundedness of Belonging

Fans ask for a specific song, artist or – more commonly – for a TikTok dedicated to themselves, their kin, or their wilāya (district). In so doing, they proudly call attention to offline geographical origin and social relations inside online spaces. For example, a fan might comment «didikas khoya sohaib (bartout)» (didikas for my brother Sohaib (Bartout)). Audiences thus turn their comment into a gift for relatives or their communities and simultaneously get to enjoy a performance in their favorite genre. The performer directly responds to the fan’s comment with a gift in the form of a TikTok. At the heart of the giveaway is the highly celebrated genre raï, which represents young people’s refined class taste. Algerian youth who admire these TikToks send them to others, whereupon the maker gains prestige in return.

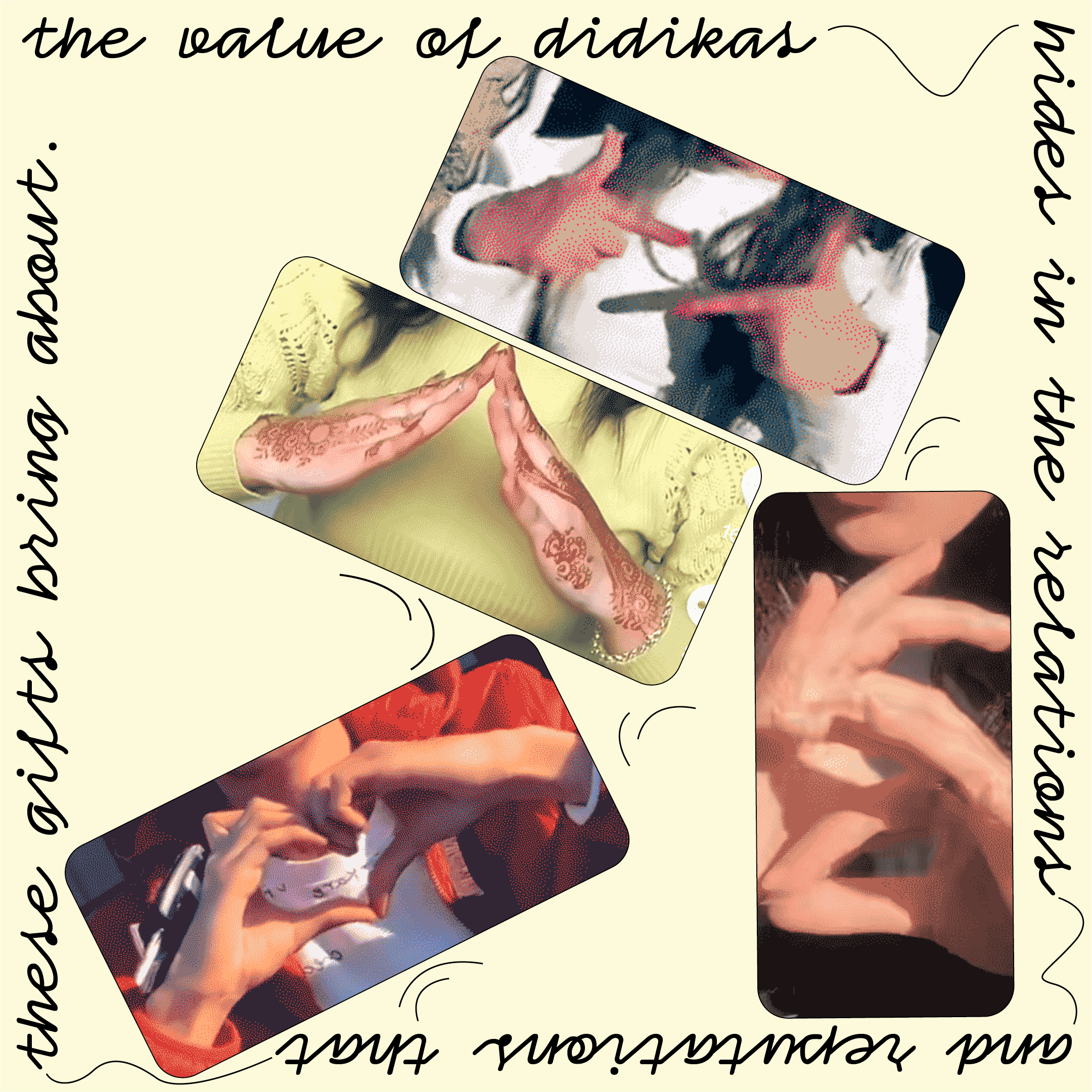

Like in Bronisław Malinowski’s ethnography of the kula in the Trobriand Islands – a ceremonial exchange of gifts that demonstrates the social value of objects beyond exchange and utility – the value of didikas lies in the relations and reputations that these gifts bring about. Sonic gifts are meaningful to young people who seek intimacy in a geographically dispersed digital network. On the one hand, the gifts represent translocal performance styles through which young people share a sense of belonging with Algerians at greater distance. On the other hand, through gifts, young people sustain intimate local networks with those nearby. In a viral world, sounds make life endurable and gratification lasting.

List of References

Biography

Links

Published on March 25, 2022

Last updated on February 01, 2023

Topics

A form of attachement beyond categories like home or nation but to people, feelings, or sounds across the globe.

From breakdance in Baghdad, the rebel dance pantsula in South Africa to the role of intoxications in club music: Dance can be a form a self-expression or self-loosing.

Digitization means empowerment: for niche musicians, queer artists and native aliens that connect online to create safe spaces.

From Korean visual kei to Brazilian rasterinha, or the dangers of suddenly rising to fame at a young age.

Snap